Nmap is one of the most commonly used network enumeration tools used in the cybersecurity landscape. Through various methods, it allows users to perform host discovery, port scanning, and gain key insights about the devices that are being scanned. The utility the program offers makes it indispensable from a cybersecurity professional toolkit, but the same could be said for malicious actors as well. Often, nmap is used by them to find a way into a network, or discover what is inside a network once they’ve gained access. This fact makes it essential for cybersecurity professionals to understand the nuts and bolts of how nmap scans work, and how to detect them.

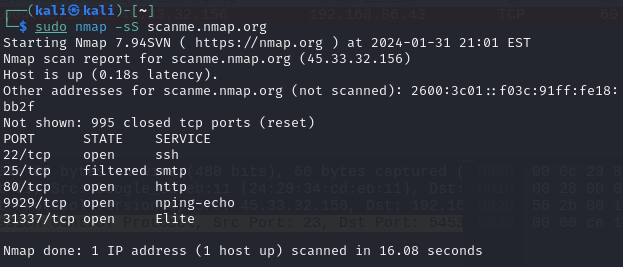

The most commonly used nmap scan is a SYN scan. Denoted by the -sS option flag, this scan is used to identify the status of ports on a machine. Open ports can act as entry points to a system, so identifying them is a must for both red and blue teamers alike. An example of this scan can be seen below:

Here, we are performing a SYN scan against scanme.nmap.org to determine which ports it has open. The way nmap does this is by sending out a SYN packet to each of the top 1000 most commonly used ports on our target device. If the port is open, closed, or being filtered by something like a firewall, we will get a different response. The scan above shows that out of 1000 ports, 4 are opened and 1 is being filtered. To understand just how nmap is able to determine the status of all these ports, we can boot up wireshark and analyse what exactly is happening.

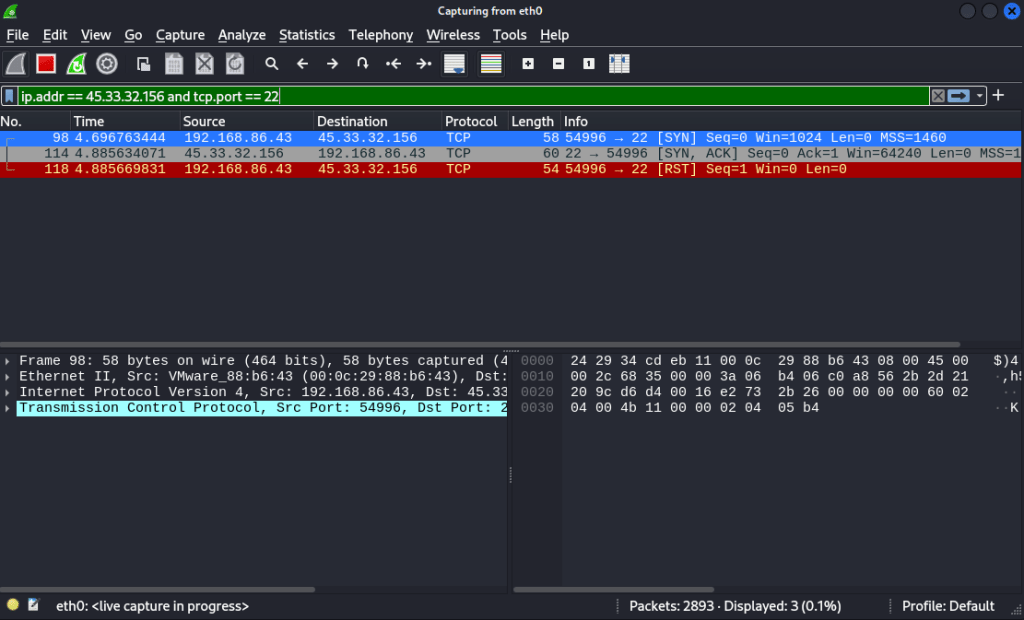

In this image, we’re using wireshark to filter for activity on port 22 of our target, one of the ports we know is open. Once our SYN packet of our scan is received by our target on port 22, it sends back a SYN/ACK packet, indicating that they are ready to initiate a TCP connection over this port. Since the target machine was willing to have a connection be established over this port, nmap understands it to be open. Once our device receives this, it immediately sends a RST packet back. This type of scan does not complete the TCP handshake, so once the SYN/ACK is received, nmap has all the information it needs and the connection can be terminated.

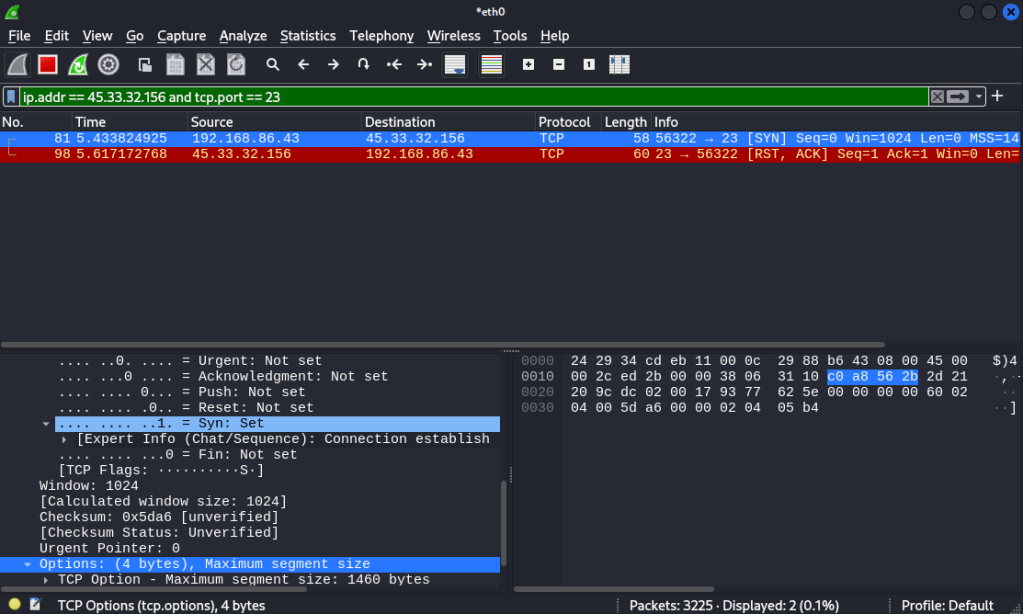

Alternatively, if the port is closed, we see a different packet conversation between our machine and the target:

Nmap determined port 23 as closed, so when we change our filter in wireshark to investigate traffic going to port 23 on that device, we can see why. The initial SYN packet is simply met with a RST/ACK packet from the target, indicating the port is closed. No further data can be transmitted to that port, since the target device will not accept connections on it.

Understanding how the SYN scan works on a packet level allows us to appreciate why it has come to be known as the stealth scan. It does not create a full TCP connection with the device’s open port, simply leaving the connection half-open. By not completing the TCP handshake, the device may not log the scan as there was no connection made.

However, many modern intrusion detection systems and firewalls are well equipped to detect SYN scans like this, so the stealth scan title isn’t as applicable in modern times. Even equipped with a packet analysis tool like wireshark, SYN scans can be identified quite easily if you know what to look for.

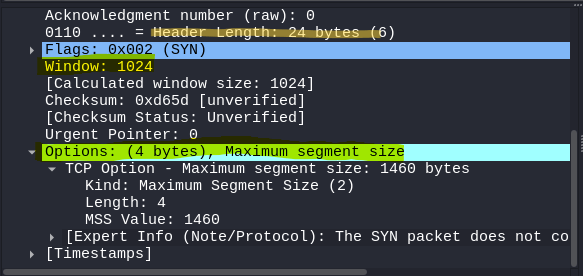

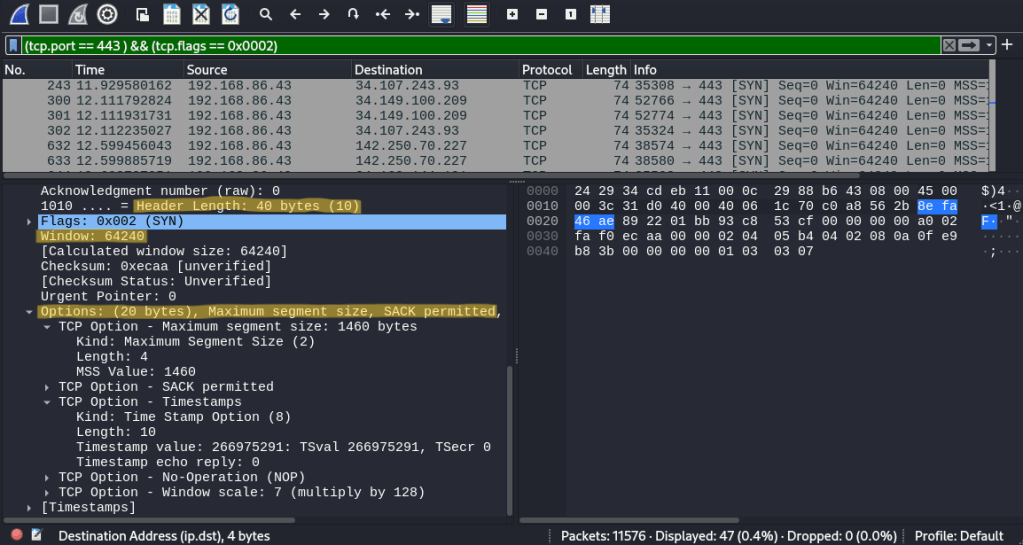

This is where our mentality shifts to a blue team mindset, aiming to identify if a scan is taking place against our network or devices. By delving into the details of the initial SYN packets sent by nmap, we can identify some key pieces of data that help us to identify if someone is performing a basic SYN scan against our devices. The pieces of data are the window size and the options field, which then in turn impacts the header length of the packet. All this is highlighted in yellow below:

Compared to regular network traffic that happens between devices, these fields are considerably abnormal. Try see how they compare to a SYN packet that was sent when I connected to google.com

Observing the two packets side by side really makes the SYN packet from nmap stand out as irregular. The window size from nmap is considerably tiny compared to a legitimate SYN packet, and the lack of options present in nmap’s SYN packet causes the header length to vary by a significant amount of bytes. These differences occur due to the fact nmap itself is sending out the SYN packets used in its scan. It is filling the packet with data itself, which makes it noticeably different from regular traffic. On the other hand, SYN packets used for regular traffic are created by the operating system, which is why they have different fields and values.

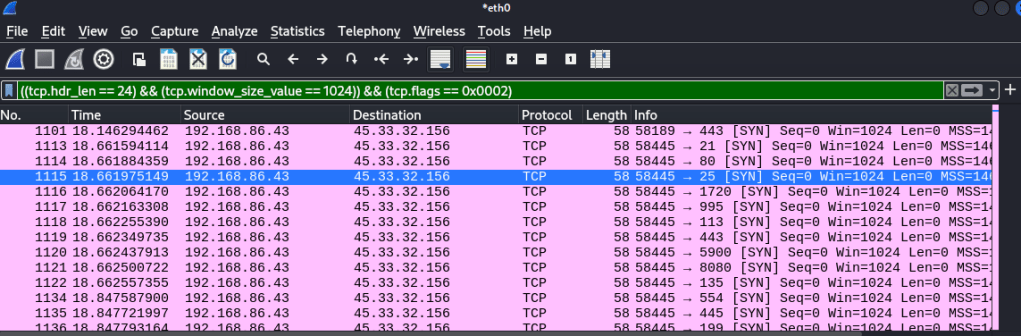

With these differences in mind, we can use this to create a filter in wireshark to catch all the SYN packets sent out by nmap using this scan. If I was a network administrator and was seeing packets like this being sent out across the network, it would definitely raise the suspicions that someone is scanning the network. The filter to do so can be seen below, which is solely catching SYN packets sent out by nmap.

However, while this may catch someone running a basic SYN scan, malicious actors are always capable of creating new ways of bypassing detection. They could use a different scan that flies under the current detection rule, or edit the values in the SYN packet so the header length is different, resulting in bypassing our previously created filtering rule.

While the filtering that we created for these scans may be easy to circumvent, the exercise still allows for a great opportunity to learn how exactly nmap functions below the surface. In general, understanding how things work from a packet level is a great way to build understanding, and create solid foundations that will serve you well as you continue to explore and investigate new and exciting things in the field. I encourage everyone with an interest in cybersecurity to play around with tools like nmap and wireshark just like this, as getting down into the nitty gritty of how exactly they work is the perfect way to build up that important knowledge base and avoid being just another script kiddie.