Welcome back! One of the videos as of late that caught my eye was this one by nang, taking a basic look into the world of reverse engineering. His video inspired me to have a go myself with some basic reverse engineering and to have a crack at some of the challenges available for download at crackmes.one. This website hosts a variety of downloadable reverse engineering challenged, with varying levels of complexity. In this post today, I’m outlining the steps I took to complete my very first CrackMe, Funny_Gopher’s StupidCrackMe, a basic CrackMe that’s linked here.

The tools I used were VirusTotal to scan the executable for malware and Ghidra as the software reverse engineering suite. This was one of the recommended pieces of software I use for reverse engineering, allowing me to decompile and disassemble the CrackMe executable and figure out what’s going on under the hood. I only have a basic understanding of the software for now, but it does look very powerful.

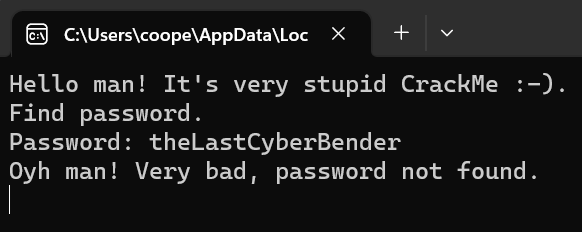

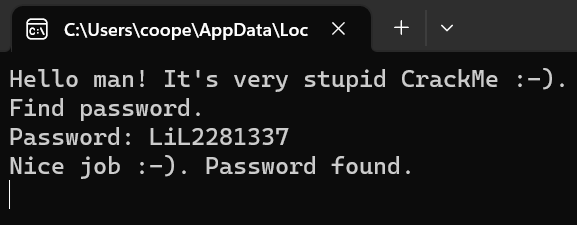

First step is to run the CrackMe and see what kind of problem we’re dealing with. Upon running, it’s a guess the password type problem, which returns the following when the wrong password is guessed.

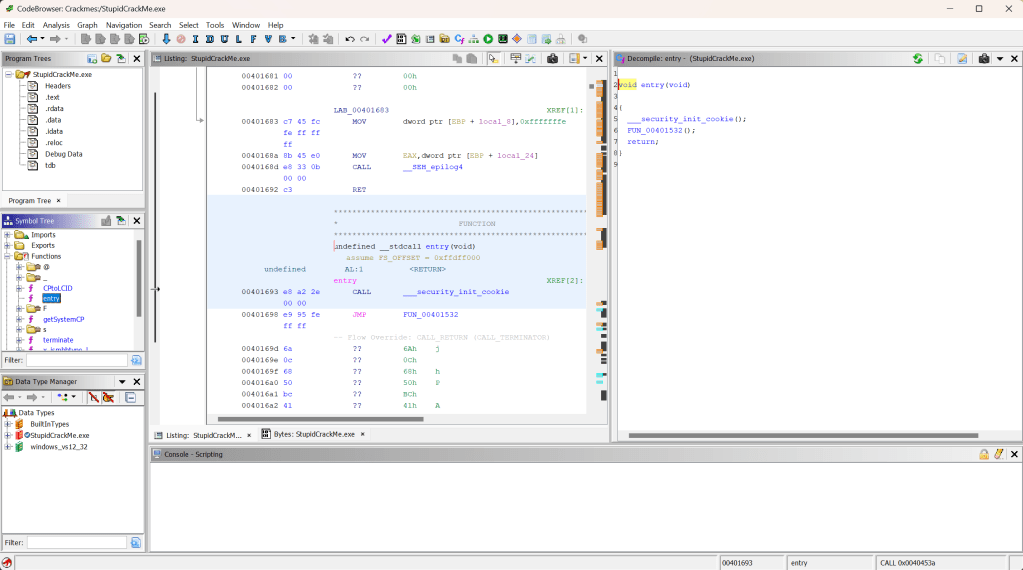

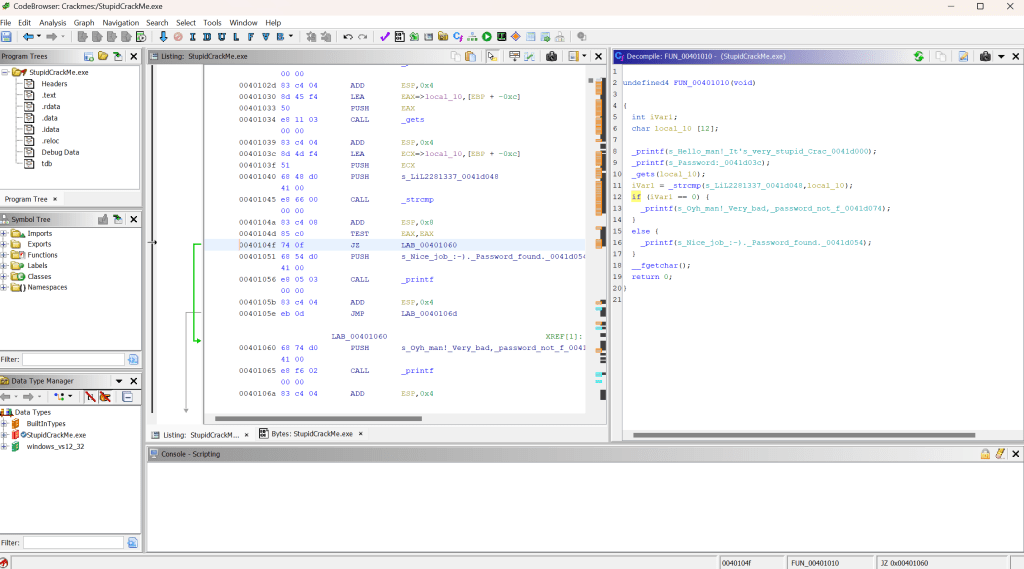

Hmm, not much I can do here besides brute force my way in, time to load the executable into a new Ghidra project, analyse it and then playing around with its decompiled form. Having a scroll through does make the program seem quite confusing, but the most important thing I’ve found in Ghidra is being able to understand and extract the information most important to you. Since the program is written in C/C++, it will have some kind of main() function, acting as the entry point for the program. This can be found under the ‘Functions’ folder, in the ‘Symbol Tree’ window on the left.

On first look, there doesn’t seem to be a main function, rather just an entry function. This appears to be the start point for the program, and the main body of the program would be further hidden within the function calls. That would involve looking through both the functions specified on the right in the decompile window to try find it however, which doesn’t seem efficient.

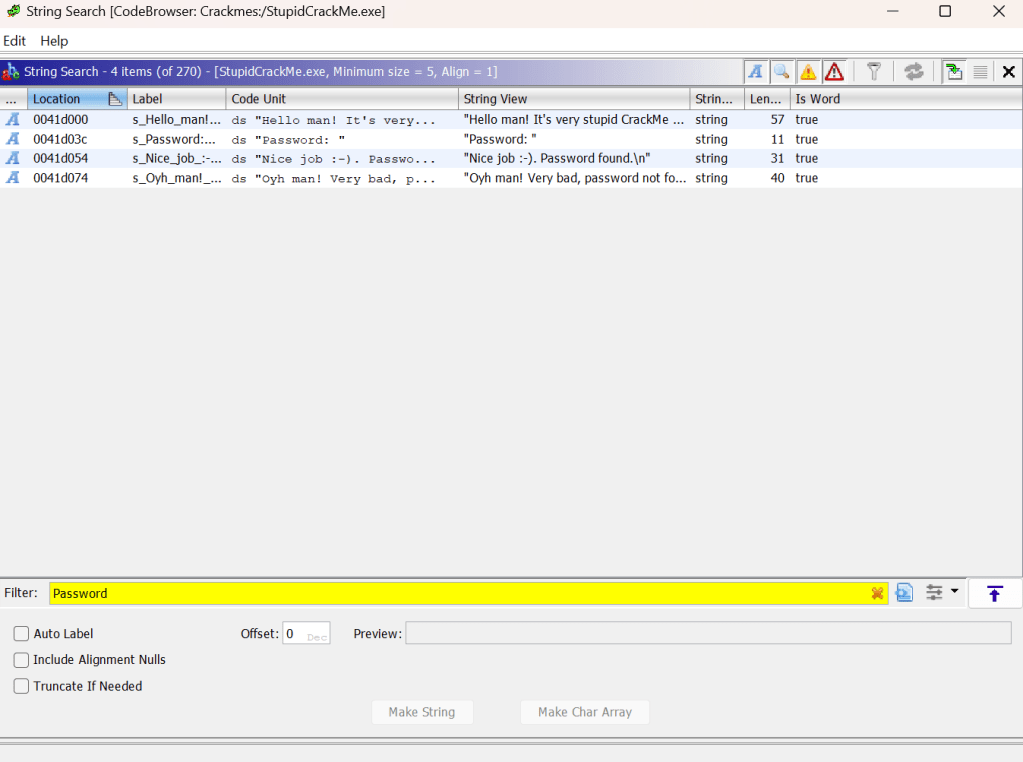

Instead, we can leverage the information we already know about the program to hopefully help us find some information about the password. This would be the strings the program is printing out. We can see that when run, the program is printing strings such as “Find Password.” and “Oyh man! Very bad, password not found.” into the terminal, so by looking for these strings, we can find out how and where they’re being used. Using string search with the filter of “Password” does just this, highlighting where in memory these strings are assigned!

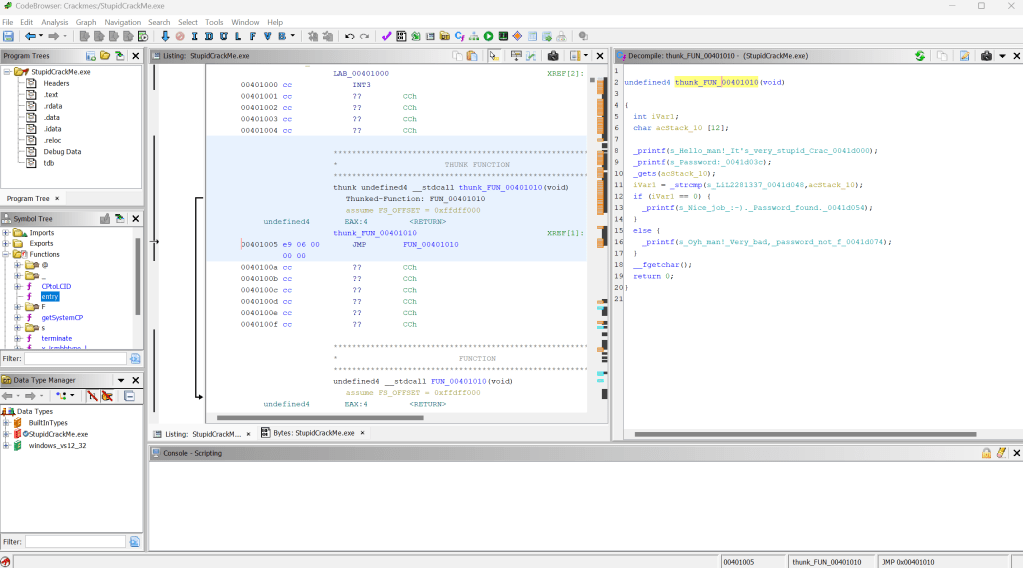

Double clicking on any of these strings takes us to the function where these strings are being used, which luckily for us contains some really great information about what the password is.

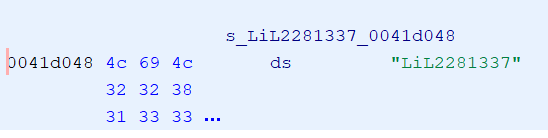

Looking at the decompiled code, we can see that the program is getting the password we’re inputting with get(), then comparing it to the actual password with strcmp(). Since our password is being stored in the acStack_10 variable, that must mean the actual password is stored within the first variable of the string compare function. Double clicking on it takes us to the memory address of the variable, showing the value to be “LiL2281337”.

Running the program once again with that gives us…

Success! CrackMe complete! Yet is there any way for us to change the program so an incorrect password would be accepted? Not just LiL2281337? We can do this by modifying the assembly code in Ghidra, allowing us to create a patched version. Clicking on the if statement in the decompiled code highlights the associated assembly code in the Listing window in the centre. Currently, the instruction is JNZ, which is a conditional jump when the zero flag – a status flag representing most recent arithmetic or logical expression – is not equal to zero. Simply, it will jump to a different part of the program if the value is not zero, which in this case, is the part of the program indicating the password is incorrect.

The opposite of this instruction is JZ, which does the same function as JNZ, except jumping when the zero flag is equal to 0. Swapping the JNZ instruction to JZ would invert the if statement, making an incorrect password the correct one, and the single correct password the incorrect one. To do so, we right click on the JNZ command and select ‘Patch Instruction’. Editing the JNZ to JZ and hitting enter will invert the if statement, which is reflected in the decompile window on the right.

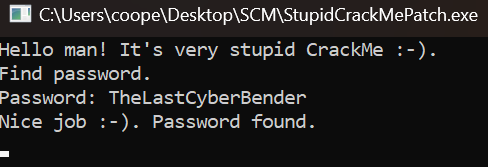

Easily done, now we just need to export the new patch as a portable executable (PE), save it and give it a try…

Working great! Just like that we’ve reversed engineered the program, so any password we use – besides the original correct one – will be seen as correct and allows us to circumvent the password check.

While this was a simpler CrackMe, it was a good starter in the world of reverse engineering, allowing me to get some good exposure to assembly and decompiler software such as Ghidra. Keen to try some more of these and progressively move up to some more complex ones, so expect to see some more posts about further CrackMes that I complete. Until then!